This article may contain links to products and services we use and recommend. We may receive compensation when you click on links to those products. For more information, see our Disclosure Policy.

To halt global warming, we (collectively) must achieve NET ZERO carbon emissions by 2050 (and significantly reduce other greenhouse gas emissions). That target doesn’t just apply to countries or specific industries. It applies to EVERY SINGLE ONE OF US.

But how many of us know what our household carbon emissions are? We certainly didn’t.

With carbon illiteracy a significant reason we (collectively) struggle to make meaningful headways in reducing emissions, we decided to

- learn more about our carbon footprint and

- find out how our lifestyle choices impact our carbon emissions.

Here is what we discovered.

To achieve NET ZERO by 2050, we all must review our lifestyle choices

Firstly, How did we calculate our carbon footprint?

Determining your carbon footprint when you’re a digital nomad is difficult.

We initially tried a few carbon footprint calculators but quickly discovered their shortcomings. We were able to use them to get a rough idea of our carbon emissions in Sydney (where we led a typical life with a fixed address), but we hit a roadblock as soon as we tried to use them for our nomadic/more alternative lifestyles.

So, we decided to calculate our carbon footprint bottom up by building a (ginormous) Excel spreadsheet and calculating each carbon contributor individually (an insane task, by the way).

We tried to take a whole lifecycle approach as much as possible, differentiating between two major groups of emissions:

- Embedded or embodied carbon: These are emissions released during the manufacturing, transport and end-of-life disposal of goods. Where goods are assets that last for a considerable amount of time, for example, accommodation (buildings, furniture, appliances), our gear (clothing, technology) or vehicles, we annualised the embodied carbon emissions based on the expected life span of the asset.

- Use/Consumption-based Emissions: As the name suggests, these are emissions released during the use of goods or the consumption of products and services. In our case, this includes our food, utilities (water, electricity, gas, internet, data storage), and transportation (based on miles travelled and transport mode/fuel consumed).

Carbon is embedded in everything we use - from the buildings we live in to the clothes on our body

Disadvantages of our bottom-up approach

We are not carbon scientists and don’t adhere to any internationally accepted carbon calculation standards. I’m sorry, but this wasn’t intended to be a scientific paper.

We don’t have access to the giant databases the experts have access to. This meant we had to make do with publicly available data. While there is way more data out there than only a few years ago, the sources don’t always disclose (or are too vague) the lifecycle elements they include. For example, some food-related emissions data may consist of emissions only from cradle to farmgate, neglecting (potentially substantial) emissions released during the processing, transport and display (in retail stores). We, therefore, often found that different sources stated different emissions data for seemingly the same thing. In those instances, we would use the average across the various sources.

While we tried to take a whole lifecycle approach, not having one reliable source and not knowing which lifecycle elements were included (or not) meant that our bottom-up calculation would contain duplications of emissions in some parts and omissions in others.

Advantages of our bottom-up approach

Taking the bottom-up approach allowed us to consider our emissions both at home and away to compare apples with apples between

- a nomadic lifestyle (where your life, work and travel morph into one), and

- a typical corporate lifestyle (where a large chunk of your emissions are caused during the commute, in city-centre offices, and during annual holidays overseas).

Building our spreadsheet and using the same approach across all our lifestyles meant we could compare our emissions across our different lifestyles despite likely omissions and duplications (as we would use the same data/sources and thus make the identical omissions/duplications across all lifestyles).

Carbon is also released on our daily commute, at our workplace, even when we go to the gym

So, how does our carbon footprint compare across different lifestyles (and internationally)?

Carbon emissions are measured in metric tons of CO2 released into the atmosphere. Every person causes CO2 emissions, but how we choose to live can make a huge difference in the amount of CO2 our lives contribute.

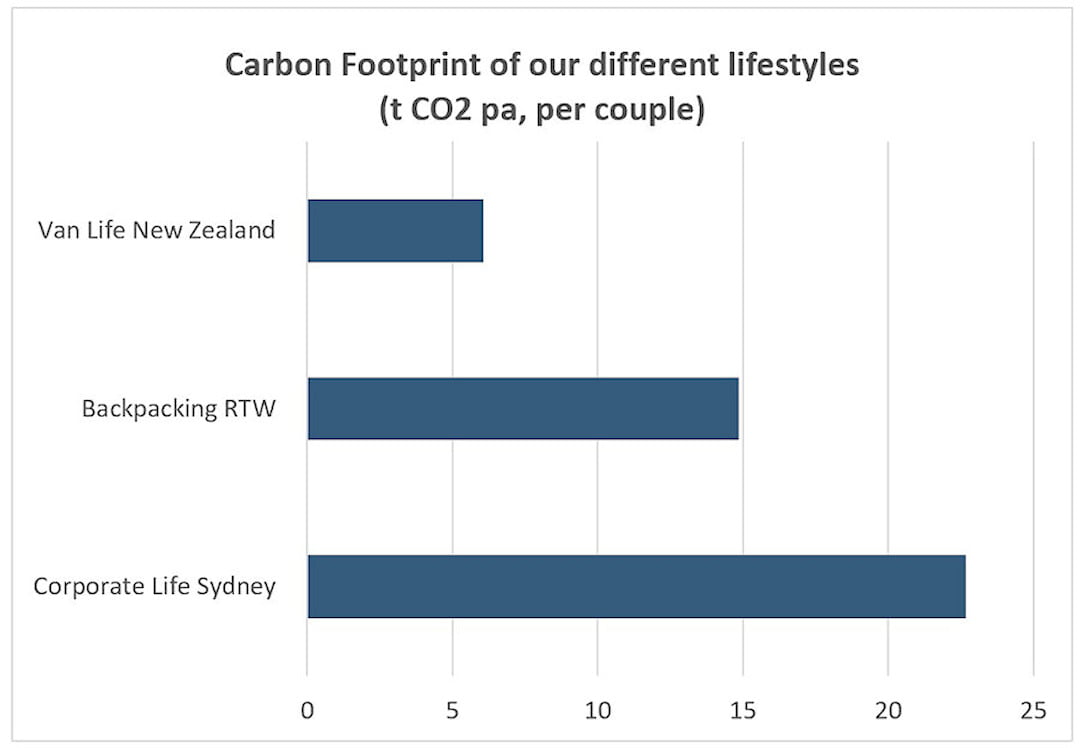

Similar to our cost of living comparison, our carbon footprint comparison shows our annual carbon emissions as a couple

- Living our corporate lives in Sydney,

- Exploring the world with carry-on travel packs and

- During our year of van life in New Zealand.

Living in a big house with a corporate job and overseas vacations caused almost four times more carbon than living in a campervan

As you can see, we emitted the most carbon in Sydney – just under 22.7 tons per annum as a couple. Backpacking around the world caused just under 14.9 tons of CO2 per annum on average. Our lowest emitting lifestyle was our year of van life in New Zealand, at just under 6.1 tons of CO2 for us.

You may not know if this is a lot or a little. So, let’s give you some perspective.

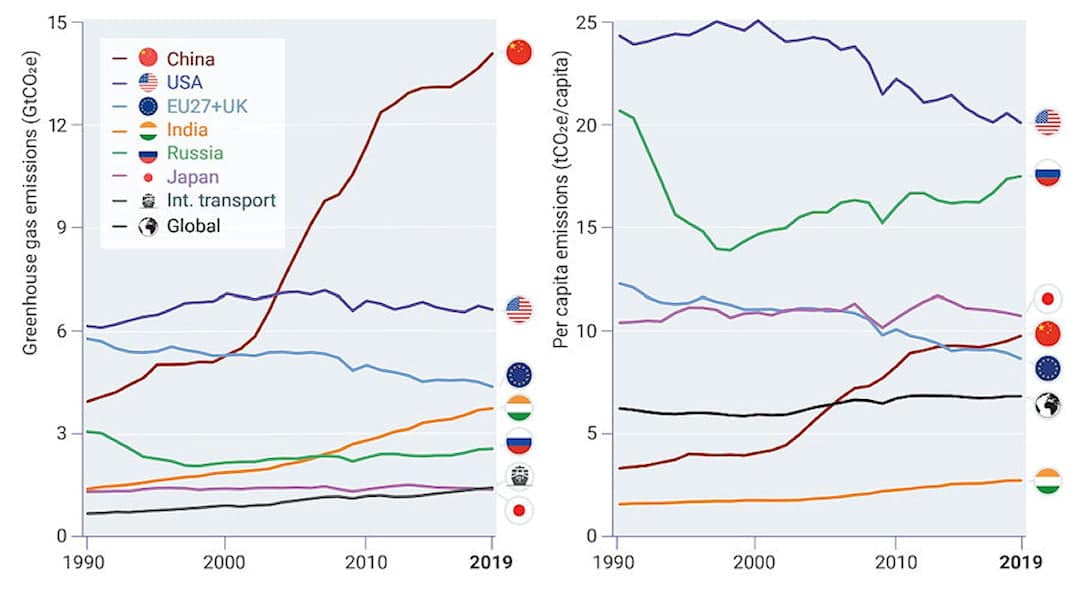

According to the latest United Nations Emissions Gap Report, the global per capita average sits at around 7 tons of CO2 (with the US as the top emitter at 20 tons of CO2 per capita):

Our corporate life in Sydney put us among the 3rd largest polluters globally | Source: UN Emissions Gap Report 2020

So, emitting 11.3 tons per person during our corporate life in Sydney puts us in the third spot (at the level of Japan). While we need to take our numbers with a grain of salt (for the above reasons), they’re still eye-opening.

If you’re wondering how your lifestyle compares to ours, here are a few more details:

Corporate Life Sydney

We lived in a 156 sqm, four-bedroom/two-bathroom terrace house in Glebe (with and without a flatmate). The house was relatively new (built in 2009), made from brick but only single-glazed (as is common in Australia). The house was fully furnished, and our wardrobes were full of clothes. Our appliances were relatively new and energy-efficient. We didn’t have air conditioning but used a gas heater on nippy winter days. We collected rainwater to water the plants in our small backyard. Otherwise, all our utilities were supplied as part of the city’s network.

We would take public transport or walk/bike to work. We didn’t own a car, but we would use a car share scheme (GoGet) for a few hours on weekends to do our weekly grocery shop or visit friends who lived on the outskirts of town.

While in Sydney, we would spend our holidays travelling locally and overseas (mostly to Europe and New Zealand to visit our families). This amounted to almost 27,000 miles per person in a typical year (or 28,000 miles per person including our daily commute).

Backpacking Round The World

We backpacked around North America and South America in 2017, around Europe in 2019, and again in 2024. In 2020 and 2021, we based ourselves in New Zealand, backpacking with the occasional house sit (as far as COVID-19 travel restrictions allowed). In all cases, we travelled with carry-on luggage only.

We would stay in homestays, locally owned guest houses, hostels and short-term rental accommodations. Or in the home of the pet owner when we house-sat. Very rarely would we stay in a hotel. We would use the appliances and heating or cooling options provided by our hosts (often sharing facilities like the kitchen, bathroom and lounge room with our hosts or other guests).

During our year in the Americas, we travelled just under 33,000 miles per person by aeroplane (including the flight from/to New Zealand). On our European journey, we travelled 36,500 miles per person by plane (again, including the return flight from/to New Zealand). All other travel – 10,500 miles per person in the Americas and just under 9,500 miles per person in Europe – was done by train, coach, ship, and public transport (and very rarely a rented motor vehicle). While backpacking in New Zealand, we travelled 2,700 miles per person per annum by aeroplane, a bit over 2,400 miles per person per annum by motor vehicle and just under 470 miles per person per annum using other modes of transportation.

We didn’t own a house and only a motor vehicle from February 2021.

That's us with our carry-on luggage leaving Sydney in 2016

Van Life New Zealand

In 2018, we lived in a diesel-fuelled 1997 Ford Transit campervan and travelled 13,800 km around the country.

During the warmer months, we would essentially stay in free campsites. In winter, we would stay in locally owned campgrounds to have access to (on-grid) electric heating. An electric boiler – powered via the engine’s alternator (while driving) or from the grid (when we stayed at paid campgrounds) – heated our water. Three 100W solar panels covered all our other electricity needs. We would cook meals on a two-burner gas stove/grill running on LPG/propane.

Again, we didn’t own a house and only owned the campervan for one year. The campervan contained the in-built furniture, our carry-on luggage and a few household items.

MJ - our trusted Ford Transit Campervan in which we travelled around New Zealand in 2018

What key insights did we gain from calculating our carbon footprint?

Learning #1

As mentioned above, online carbon footprint calculators do not (yet) cater to nomadic/alternative lifestyles. Most smaller houses are still more significant than tiny houses, and even car sharing is a concept they don’t accommodate.

Learning #2

None of our lifestyles meets the United Nations per capita average targets of 2.1t pp pa by 2030. The closest we’ve gotten to that target was during our year of van life in New Zealand when we had just over three tons per person per annum.

Learning #3

Our corporate life (with overseas holidays) was more carbon-intensive than our alternative/nomadic lifestyles.

Learning #4

Transportation is the most significant cause of our carbon emissions – across all our lifestyles:

Transportation is the biggest contributor to our carbon footprint, causing 49-71% of our emissions

We expected that for our backpacking lifestyles, as we took a lot of aeroplanes (and to travel anywhere from New Zealand, you had to jump on an aeroplane or a (cruise)ship—which isn’t environmentally friendly either).

A surprise to us, though, was that travelling halfway around the world for a two-week vacation and taking several shorter flights closer to home emitted almost as much carbon as spending a whole year overseas and travelling slowly (all data is per couple per annum):

- Corporate Life Sydney – Holiday and business travel (10.8 tons), daily commute on public transport (0.4 tons)

- Backpacking RTW – Average of

- Backpacking Americas (13.9 tons),

- Backpacking Europe (15.3 tons) and

- Backpacking New Zealand (2.0 tons)

- Van Life New Zealand – 3.0 tons.

Learning #5

Apart from cost savings, the sharing economy has a huge environmental benefit. Embodied and energy-use-related carbon emissions are reduced significantly when we share assets like accommodation, appliances, vehicles, tools, etc.

Learning #6

Beyond our carbon footprint, we gained deep insight into our water consumption. We consumed 263 litres per person per day in Sydney but only 32 litres per person per day during our year of van life in New Zealand.

When we lived in our campervan, we used less than 1/8 of the water we consumed in Sydney

Learning #7

We gained a few other surprising insights:

- Agriculture is a huge contributor to carbon emissions, more than we realise. Livestock emissions account for 14.5% of greenhouse gas emissions globally. Animal protein production is highly carbon-intensive (especially if you consider that only 40-65% of an animal is edible).

- Aviation is often called the main culprit of carbon emissions. But air travel (only) accounts for 2.5% of global CO2 emissions. A far larger culprit is road transport, which accounts for 78% of all transport emissions (compared to 8% for air transport). Short-haul flights generally emit more than medium and long-haul flights. However, actual emissions also depend on the type of aeroplane used. 80% of aviation emissions come from flights over 1,500 kilometres (medium- and long-haul).

- While air travel always gets blamed, the fashion industry somehow slips under the radar. Yet, the fashion industry contributed 4% of global greenhouse gas emissions in 2018 (almost 3/4 of which were generated before items reached retail stores).

Did you know that fast fashion has a bigger carbon footprint than aviation?

How will these learnings impact our lifestyle choices in the future?

Sustainability is one of our shared core values. Since we started living nomadic/alternative lifestyles, we’ve become much more mindful of our water and energy consumption and the environmental and social impact of our purchases. However, our carbon footprint is way above the UN per-capita targets, which shows us that we need to do more.

Nomadic Life

While we want to continue living nomadically (health and finances permitting), we will reduce the amount we fly and (continue to) choose alternative, more environmentally friendly modes of transportation as much as possible. Tools like Eco Passenger will help us choose the most appropriate option.

Overlanding around the world was our plan before COVID-19 hit, and it is still something we may do in the future. We now have the Microsoft Excel spreadsheet to calculate whether it is more environmentally friendly to slowly overland in a diesel vehicle (with the occasional ship/ferry) or backpack (with ground transportation and the occasional long-haul flight). Based on our findings, we will either

use existing public ground transportation as much as possible and only hire a (fuel-efficient) vehicle when required, or select the most fuel-efficient vehicle for our needs and live otherwise off-grid with solar.

By understanding our carbon footprint we can make better decisions about our travels in future

Post-Nomadic Life

We know that at some point, we may want (or need) to spend more time in one spot (and only travel occasionally). While we could see ourselves living in several countries around the globe, we’ll likely end up in New Zealand (where Paul is from).

To accommodate this possibility (and not be priced out of the market), in 2021, we purchased a plot of bare land in New Zealand. Over time, we intend to transform the land into a small permaculture farm that allows us to grow our food (to be reasonably self-sufficient) and share surplus food with our local community. We would live in a tiny house and share the farm with other like-minded people.

Since purchasing the land, we have installed rainwater tanks (our only freshwater source) and a worm-farm-based wastewater system that allows us to recycle and reuse our wastewater for plant irrigation. We compost all our organic and most of our paper/cardboard waste.

Our tiny house will be designed to minimise heating and cooling needs in winter and summer. Appliances (including heating and cooling for the hopefully rare occasions we need them) will be as energy-efficient, low-emission, and water-efficient as possible.

While our land is connected to the grid, we want to move our power supply to renewable electricity. We may also install a solar and/or wind energy system at some stage in the future. [Update 13 January 2022: We switched to Ecotricity, a carbon-zero energy provider. 100% of our electricity now comes from solar, wind and hydro.)]

Given our land is in a rural location without public transport, living on the land will require our own mode of transportation. We would purchase an electric vehicle if/when we live on the land (more or less) full-time. By then (hopefully), electric vehicles will be more commonplace and affordable.

When we need a vehicle, we'll be looking for the most environmentally friendly one we can afford

General

Whether nomadic or not, we are changing our diet. Over the past five years, we have already reduced our consumption of dairy and meat. In the future, we will forego dairy products altogether and only have one meat-based meal per week.

We won’t be able to track our carbon footprint as we track our finances (though one day, thanks to CO2 emissions labelling for products, we might). However, we will use our calculation spreadsheet and keep track of our emissions annually to ensure we are heading in the right direction.

Over time, we also intend to offset our (remaining) carbon emissions by planting (more) trees and shrubs on our land. Since purchasing the land, we have planted around 350 shrubs and trees (86% are New Zealand natives). And we will continue growing and rewilding the land for many years.

We are removing dairy products from our diet and only have one meat-based meal per week

Recommended Books on Adopting Minimalism

- Dean Christopher's Minimalism leads readers through a 12-week process designed to help them identify their values, evaluate their habits, change their mindsets, reduce their mental stress, and ultimately transform their lives.

- Mastering Minimalism by Jordan Williams provides a comprehensive roadmap to those seeking to adopt minimalism by taking a holistic, wheel-of-life approach that covers all aspects of our lives.

- Cal Newport's Digital Minimalism explores the impact of constant connectivity. It helps us regain control by using technology to support our values and goals (not distracting from them).

- Travel Light by Light Watkins combines the principles of minimalism with the art of travel. It offers practical tips on planning, packing, and staying mindful on the road to enhance the experience.

- Sustainable Living Minimalism and Zero Waste by B R Pohl focuses on the intersection of minimalism and sustainability, helping readers to limit their footprint by reducing waste and consuming (more) mindfully.

What can you learn from it?

Our carbon footprint is unique to us. And our lifestyle choices may be very different from your own. But we believe there are still learnings you can take away from this article:

Measure

Understand your starting point by calculating your carbon footprint. Here are some carbon footprint calculators to get you started (alphabetically, based on your location):

| United States | New Zealand | Australia | Europe | Anywhere |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Footprint Ltd Conservation International CoolClimate EPA The Nature Conservancy | Future Fit Toitu Envirocare | Carbon Neutral Carbon Positive | My Climate WWF Germany WWF UK | Global Footprint Network WikiHow Wren - which offers a calculator and carbon offset in one convenient solution |

Reduce

Be more mindful of your everyday actions’ environmental footprint. Then, determine what specific actions you can take to (significantly) reduce your carbon footprint.

The best way to reduce carbon in the atmosphere is by not emitting it in the first place (Gabriela Herculano)

For those interested in some in-depth research on how lifestyle choices impact your carbon footprint:

"The best way to reduce carbon in the atmosphere is by not emitting in the first place" (G Herculano)

Offset

Plant trees in your garden or neighbourhood. In absence of that, find projects that remove carbon from the atmosphere, for example:

- (kelp) forest regeneration projects like Just One Tree,

- the projects of the Borneo Nature Foundation or

- The Wren Climate Fund is a hand-picked portfolio that includes reforestation and land restoration projects but also invests in the development of new carbon sequestration methods and technologies (like turning dead undergrowth into biochar, which reduces the risk of wildfires at the same time).

Look for certified projects and projects run by not-for-profits to ensure every cent has an impact.

What Carbon Calculators do you use?

If you know your household carbon footprint:

- What calculator/s did you use, and how much CO2 do you emit per year?

- What changes to your lifestyle have you made to reduce your carbon emissions?

Before you go, if you liked our article and found it helpful, we would appreciate it if you could share it with your friends and family via the Share buttons below. Even better: Leave a short review on Trustpilot or Google, which would help us further build our online reputation as a (trustworthy and helpful) travel and lifestyle blog.